3.2.1. Introduction to Views¶

Views are useful for many purposes:

Filtering the documents in your database to find those relevant to a particular process.

Extracting data from your documents and presenting it in a specific order.

Building efficient indexes to find documents by any value or structure that resides in them.

Use these indexes to represent relationships among documents.

Finally, with views you can make all sorts of calculations on the data in your documents. For example, if documents represent your company’s financial transactions, a view can answer the question of what the spending was in the last week, month, or year.

3.2.1.1. What Is a View?¶

Let’s go through the different use cases. First is extracting data that you might need for a special purpose in a specific order. For a front page, we want a list of blog post titles sorted by date. We’ll work with a set of example documents as we walk through how views work:

{

"_id":"biking",

"_rev":"AE19EBC7654",

"title":"Biking",

"body":"My biggest hobby is mountainbiking. The other day...",

"date":"2009/01/30 18:04:11"

}

{

"_id":"bought-a-cat",

"_rev":"4A3BBEE711",

"title":"Bought a Cat",

"body":"I went to the the pet store earlier and brought home a little kitty...",

"date":"2009/02/17 21:13:39"

}

{

"_id":"hello-world",

"_rev":"43FBA4E7AB",

"title":"Hello World",

"body":"Well hello and welcome to my new blog...",

"date":"2009/01/15 15:52:20"

}

Three will do for the example. Note that the documents are sorted by “_id”, which is how they are stored in the database. Now we define a view. Bear with us without an explanation while we show you some code:

function(doc) {

if(doc.date && doc.title) {

emit(doc.date, doc.title);

}

}

This is a map function, and it is written in JavaScript. If you are not familiar with JavaScript but have used C or any other C-like language such as Java, PHP, or C#, this should look familiar. It is a simple function definition.

You provide CouchDB with view functions as strings stored inside the views

field of a design document. To create this view you can use this command:

curl -X PUT http://admin:password@127.0.0.1:5984/db/_design/my_ddoc

-d '{"views":{"my_filter":{"map":

"function(doc) { if(doc.date && doc.title) { emit(doc.date, doc.title); }}"}}}'

You don’t run the JavaScript function yourself. Instead, when you query your view, CouchDB takes the source code and runs it for you on every document in the database your view was defined in. You query your view to retrieve the view result using the following command:

curl -X GET http://admin:password@127.0.0.1:5984/db/_design/my_ddoc/_view/my_filter

All map functions have a single parameter doc. This is a single document in

the database. Our map function checks whether our document has a date and

a title attribute — luckily, all of our documents have them — and then calls

the built-in emit() function with these two attributes as arguments.

The emit() function always takes two arguments: the first is key,

and the second is value. The emit(key, value) function creates an entry

in our view result. One more thing: the emit() function can be called

multiple times in the map function to create multiple entries in the view

results from a single document, but we are not doing that yet.

CouchDB takes whatever you pass into the emit() function and puts it into a list

(see Table 1, “View results” below). Each row in that list includes the key

and value. More importantly, the list is sorted by key (by doc.date

in our case). The most important feature of a view result is that it is sorted

by key. We will come back to that over and over again to do neat things. Stay

tuned.

Table 1. View results:

Key |

Value |

|---|---|

“2009/01/15 15:52:20” |

“Hello World” |

“2009/01/30 18:04:11” |

“Biking” |

“2009/02/17 21:13:39” |

“Bought a Cat” |

When you query your view, CouchDB takes the source code and runs it for you on every document in the database. If you have a lot of documents, that takes quite a bit of time and you might wonder if it is not horribly inefficient to do this. Yes, it would be, but CouchDB is designed to avoid any extra costs: it only runs through all documents once, when you first query your view. If a document is changed, the map function is only run once, to recompute the keys and values for that single document.

The view result is stored in a B-tree, just like the structure that is responsible for holding your documents. View B-trees are stored in their own file, so that for high-performance CouchDB usage, you can keep views on their own disk. The B-tree provides very fast lookups of rows by key, as well as efficient streaming of rows in a key range. In our example, a single view can answer all questions that involve time: “Give me all the blog posts from last week” or “last month” or “this year.” Pretty neat.

When we query our view, we get back a list of all documents sorted by date. Each row also includes the post title so we can construct links to posts. Table 1 is just a graphical representation of the view result. The actual result is JSON-encoded and contains a little more metadata:

{

"total_rows": 3,

"offset": 0,

"rows": [

{

"key": "2009/01/15 15:52:20",

"id": "hello-world",

"value": "Hello World"

},

{

"key": "2009/01/30 18:04:11",

"id": "biking",

"value": "Biking"

},

{

"key": "2009/02/17 21:13:39",

"id": "bought-a-cat",

"value": "Bought a Cat"

}

]

}

Now, the actual result is not as nicely formatted and doesn’t include any superfluous whitespace or newlines, but this is better for you (and us!) to read and understand. Where does that “id” member in the result rows come from? That wasn’t there before. That’s because we omitted it earlier to avoid confusion. CouchDB automatically includes the document ID of the document that created the entry in the view result. We’ll use this as well when constructing links to the blog post pages.

Warning

Do not emit the entire document as the value of your emit(key, value)

statement unless you’re sure you know you want it. This stores an entire

additional copy of your document in the view’s secondary index. Views with

emit(key, doc) take longer to update, longer to write to disk, and

consume significantly more disk space. The only advantage is that they

are faster to query than using the ?include_docs=true parameter when

querying a view.

Consider the trade-offs before emitting the entire document. Often it is sufficient to emit only a portion of the document, or just a single key / value pair, in your views.

3.2.1.2. Efficient Lookups¶

Let’s move on to the second use case for views: “building efficient indexes to find documents by any value or structure that resides in them.” We already explained the efficient indexing, but we skipped a few details. This is a good time to finish this discussion as we are looking at map functions that are a little more complex.

First, back to the B-trees! We explained that the B-tree that backs the key-sorted view result is built only once, when you first query a view, and all subsequent queries will just read the B-tree instead of executing the map function for all documents again. What happens, though, when you change a document, add a new one, or delete one? Easy: CouchDB is smart enough to find the rows in the view result that were created by a specific document. It marks them invalid so that they no longer show up in view results. If the document was deleted, we’re good — the resulting B-tree reflects the state of the database. If a document got updated, the new document is run through the map function and the resulting new lines are inserted into the B-tree at the correct spots. New documents are handled in the same way. The B-tree is a very efficient data structure for our needs, and the crash-only design of CouchDB databases is carried over to the view indexes as well.

To add one more point to the efficiency discussion: usually multiple documents are updated between view queries. The mechanism explained in the previous paragraph gets applied to all changes in the database since the last time the view was queried in a batch operation, which makes things even faster and is generally a better use of your resources.

3.2.1.2.1. Find One¶

On to more complex map functions. We said “find documents by any value or

structure that resides in them.” We already explained how to extract a value

by which to sort a list of views (our date field). The same mechanism is used

for fast lookups. The URI to query to get a view’s result is

/database/_design/designdocname/_view/viewname. This gives you a list of all

rows in the view. We have only three documents, so things are small, but with

thousands of documents, this can get long. You can add view parameters to the

URI to constrain the result set. Say we know the date of a blog post.

To find a single document, we would use

/blog/_design/docs/_view/by_date?key="2009/01/30 18:04:11"

to get the “Biking” blog post. Remember that you can place whatever you like

in the key parameter to the emit() function. Whatever you put in there, we can

now use to look up exactly — and fast.

Note that in the case where multiple rows have the same key (perhaps we design a view where the key is the name of the post’s author), key queries can return more than one row.

3.2.1.2.2. Find Many¶

We talked about “getting all posts for last month.” If it’s February now, this is as easy as:

/blog/_design/docs/_view/by_date?startkey="2010/01/01 00:00:00"&endkey="2010/02/00 00:00:00"

The startkey and endkey parameters specify an inclusive range on which

we can search.

To make things a little nicer and to prepare for a future example, we are going to change the format of our date field. Instead of a string, we are going to use an array, where individual members are part of a timestamp in decreasing significance. This sounds fancy, but it is rather easy. Instead of:

{

"date": "2009/01/31 00:00:00"

}

we use:

{

"date": [2009, 1, 31, 0, 0, 0]

}

Our map function does not have to change for this, but our view result looks a little different:

Table 2. New view results:

Key |

Value |

|---|---|

[2009, 1, 15, 15, 52, 20] |

“Hello World” |

[2009, 2, 17, 21, 13, 39] |

“Biking” |

[2009, 1, 30, 18, 4, 11] |

“Bought a Cat” |

And our queries change to:

/blog/_design/docs/_view/by_date?startkey=[2010, 1, 1, 0, 0, 0]&endkey=[2010, 2, 1, 0, 0, 0]

For all you care, this is just a change in syntax, not meaning. But it shows you the power of views. Not only can you construct an index with scalar values like strings and integers, you can also use JSON structures as keys for your views. Say we tag our documents with a list of tags and want to see all tags, but we don’t care for documents that have not been tagged.

{

...

tags: ["cool", "freak", "plankton"],

...

}

{

...

tags: [],

...

}

function(doc) {

if(doc.tags.length > 0) {

for(var idx in doc.tags) {

emit(doc.tags[idx], null);

}

}

}

This shows a few new things. You can have conditions on structure

(if(doc.tags.length > 0)) instead of just values. This is also an example of

how a map function calls emit() multiple times per document.

And finally, you can pass null instead of a value to the value parameter.

The same is true for the key parameter. We’ll see in a bit how that is useful.

3.2.1.2.3. Reversed Results¶

To retrieve view results in reverse order, use the descending=true query

parameter. If you are using a startkey parameter, you will find that CouchDB

returns different rows or no rows at all. What’s up with that?

It’s pretty easy to understand when you see how view query options work under the hood. A view is stored in a tree structure for fast lookups. Whenever you query a view, this is how CouchDB operates:

Starts reading at the top, or at the position that

startkeyspecifies, if present.Returns one row at a time until the end or until it hits

endkey, if present.

If you specify descending=true, the reading direction is reversed,

not the sort order of the rows in the view. In addition, the same two-step

procedure is followed.

Say you have a view result that looks like this:

Key |

Value |

|---|---|

0 |

“foo” |

1 |

“bar” |

2 |

“baz” |

Here are potential query options: ?startkey=1&descending=true. What will

CouchDB do? See #1 above: it jumps to startkey, which is the row with the

key 1, and starts reading backward until it hits the end of the view.

So the particular result would be:

Key |

Value |

|---|---|

1 |

“bar” |

0 |

“foo” |

This is very likely not what you want. To get the rows with the indexes 1

and 2 in reverse order, you need to switch the startkey to endkey:

endkey=1&descending=true:

Key |

Value |

|---|---|

2 |

“baz” |

1 |

“bar” |

Now that looks a lot better. CouchDB started reading at the bottom of the view

and went backward until it hit endkey.

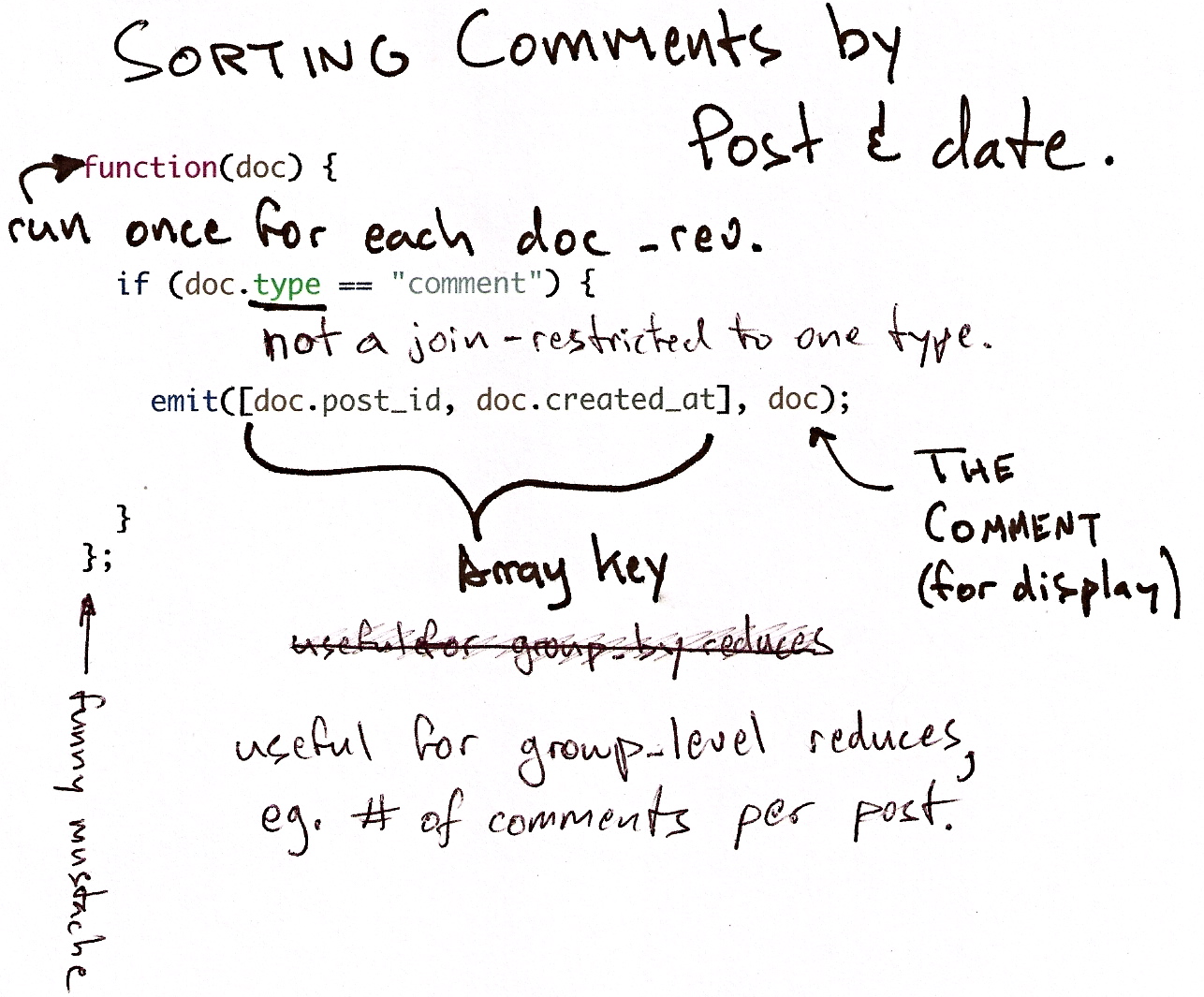

3.2.1.3. The View to Get Comments for Posts¶

We use an array key here to support the group_level reduce query parameter.

CouchDB’s views are stored in the B-tree file structure. Because of the way

B-trees are structured, we can cache the intermediate reduce results in the

non-leaf nodes of the tree, so reduce queries can be computed along arbitrary

key ranges in logarithmic time. See Figure 1, “Comments map function”.

In the blog app, we use group_level reduce queries to compute the count of

comments both on a per-post and total basis, achieved by querying the same view

index with different methods. With some array keys, and assuming each key has

the value 1:

["a","b","c"]

["a","b","e"]

["a","c","m"]

["b","a","c"]

["b","a","g"]

the reduce view:

function(keys, values, rereduce) {

return sum(values)

}

or:

_sum

which is a built-in CouchDB reduce function (the others are _count and

_stats). _sum here returns the total number of rows between the start

and end key. So with startkey=["a","b"]&endkey=["b"] (which includes the

first three of the above keys) the result would equal 3. The effect is to

count rows. If you’d like to count rows without depending on the row value,

you can switch on the rereduce parameter:

function(keys, values, rereduce) {

if (rereduce) {

return sum(values);

} else {

return values.length;

}

}

Note

The JavaScript function above could be effectively replaced by the built-in

_count.

Figure 1. Comments map function¶

This is the reduce view used by the example app to count comments, while

utilizing the map to output the comments, which are more useful than just

1 over and over. It pays to spend some time playing around with map and

reduce functions. Fauxton is OK for this, but it doesn’t give full access to

all the query parameters. Writing your own test code for views in your language

of choice is a great way to explore the nuances and capabilities of CouchDB’s

incremental MapReduce system.

Anyway, with a group_level query, you’re basically running a series of

reduce range queries: one for each group that shows up at the level you query.

Let’s reprint the key list from earlier, grouped at level 1:

["a"] 3

["b"] 2

And at group_level=2:

["a","b"] 2

["a","c"] 1

["b","a"] 2

Using the parameter group=true makes it behave as though it were

group_level=999, so in the case of our current example, it would give the

number 1 for each key, as there are no exactly duplicated keys.

3.2.1.4. Reduce/Rereduce¶

We briefly talked about the rereduce parameter to the reduce function.

We’ll explain what’s up with it in this section. By now, you should have learned

that your view result is stored in B-tree index structure for efficiency.

The existence and use of the rereduce parameter is tightly coupled to how

the B-tree index works.

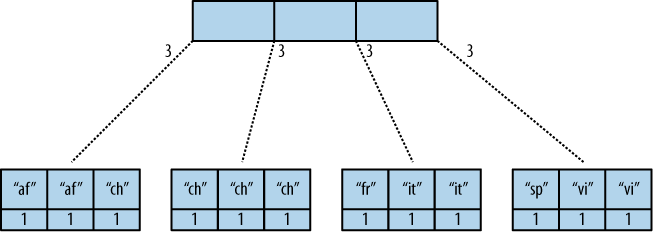

Consider the map result are:

"afrikaans", 1

"afrikaans", 1

"chinese", 1

"chinese", 1

"chinese", 1

"chinese", 1

"french", 1

"italian", 1

"italian", 1

"spanish", 1

"vietnamese", 1

"vietnamese", 1

Example 1. Example view result (mmm, food)

When we want to find out how many dishes there are per origin, we can reuse the simple reduce function shown earlier:

function(keys, values, rereduce) {

return sum(values);

}

Figure 2, “The B-tree index” shows a simplified version of what the B-tree index looks like. We abbreviated the key strings.

Figure 2. The B-tree index¶

The view result is what computer science grads call a “pre-order” walk through the tree. We look at each element in each node starting from the left. Whenever we see that there is a subnode to descend into, we descend and start reading the elements in that subnode. When we have walked through the entire tree, we’re done.

You can see that CouchDB stores both keys and values inside each leaf node.

In our case, it is simply always 1, but you might have a value where you

count other results and then all rows have a different value. What’s important

is that CouchDB runs all elements that are within a node into the reduce

function (setting the rereduce parameter to false) and stores the result

inside the parent node along with the edge to the subnode. In our case, each

edge has a 3 representing the reduce value for the node it points to.

Note

In reality, nodes have more than 1,600 elements in them. CouchDB computes the result for all the elements in multiple iterations over the elements in a single node, not all at once (which would be disastrous for memory consumption).

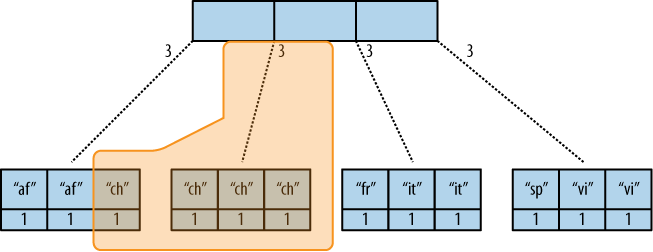

Now let’s see what happens when we run a query. We want to know how many

“chinese” entries we have. The query option is simple: ?key="chinese".

See Figure 3, “The B-tree index reduce result”.

Figure 3. The B-tree index reduce result¶

CouchDB detects that all values in the subnode include the “chinese” key.

It concludes that it can take just the 3 values associated with that node to

compute the final result. It then finds the node left to it and sees that it’s

a node with keys outside the requested range (key= requests a range where

the beginning and the end are the same value). It concludes that it has to use

the “chinese” element’s value and the other node’s value and run them through

the reduce function with the rereduce parameter set to true.

The reduce function effectively calculates 3 + 1 at query time and returns the desired result. The next example shows some pseudocode that shows the last invocation of the reduce function with actual values:

function(null, [3, 1], true) {

return sum([3, 1]);

}

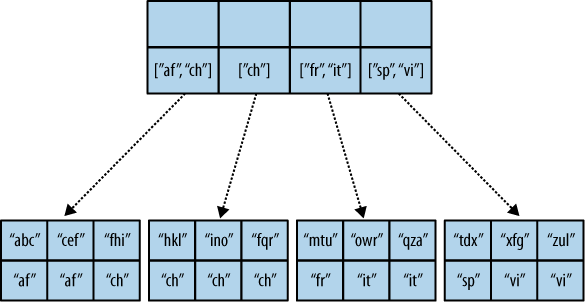

Now, we said your reduce function must actually reduce your values. If you see the B-tree, it should become obvious what happens when you don’t reduce your values. Consider the following map result and reduce function. This time we want to get a list of all the unique labels in our view:

"abc", "afrikaans"

"cef", "afrikaans"

"fhi", "chinese"

"hkl", "chinese"

"ino", "chinese"

"lqr", "chinese"

"mtu", "french"

"owx", "italian"

"qza", "italian"

"tdx", "spanish"

"xfg", "vietnamese"

"zul", "vietnamese"

We don’t care for the key here and only list all the labels we have. Our reduce function removes duplicates:

function(keys, values, rereduce) {

var unique_labels = {};

values.forEach(function(label) {

if(!unique_labels[label]) {

unique_labels[label] = true;

}

});

return unique_labels;

}

This translates to Figure 4, “An overflowing reduce index”.

We hope you get the picture. The way the B-tree storage works means that if you don’t actually reduce your data in the reduce function, you end up having CouchDB copy huge amounts of data around that grow linearly, if not faster, with the number of rows in your view.

CouchDB will be able to compute the final result, but only for views with a few rows. Anything larger will experience a ridiculously slow view build time. To help with that, CouchDB since version 0.10.0 will throw an error if your reduce function does not reduce its input values.

Figure 4. An overflowing reduce index¶

3.2.1.5. One vs. Multiple Design Documents¶

A common question is: when should I split multiple views into multiple design documents, or keep them together?

Each view you create corresponds to one B-tree. All views in a single design document will live in the same set of index files on disk (one file per database shard; in 2.0+ by default, 8 files per node).

The most practical consideration for separating views into separate documents is how often you change those views. Views that change often, and are in the same design document as other views, will invalidate those other views’ indexes when the design document is written, forcing them all to rebuild from scratch. Obviously you will want to avoid this in production!

However, when you have multiple views with the same map function in the same

design document, CouchDB will optimize and only calculate that map function

once. This lets you have two views with different reduce functions (say,

one with _sum and one with _stats) but build only a single copy

of the mapped index. It also saves disk space and the time to write multiple

copies to disk.

Another benefit of having multiple views in the same design document is that the index files can keep a single index of backwards references from docids to rows. CouchDB needs these “back refs” to invalidate rows in a view when a document is deleted (otherwise, a delete would force a total rebuild!)

One other consideration is that each separate design document will spawn

another (set of) couchjs processes to generate the view, one per shard.

Depending on the number of cores on your server(s), this may be efficient

(using all of the idle cores you have) or inefficient (overloading the CPU on

your servers). The exact situation will depend on your deployment architecture.

So, should you use one or multiple design documents? The choice is yours.

3.2.1.6. Lessons Learned¶

If you don’t use the key field in the map function, you are probably doing it wrong.

If you are trying to make a list of values unique in the reduce functions, you are probably doing it wrong.

If you don’t reduce your values to a single scalar value or a small fixed-sized object or array with a fixed number of scalar values of small sizes, you are probably doing it wrong.

3.2.1.7. Wrapping Up¶

Map functions are side effect–free functions that take a document as argument

and emit key/value pairs. CouchDB stores the emitted rows by constructing a

sorted B-tree index, so row lookups by key, as well as streaming operations

across a range of rows, can be accomplished in a small memory and processing

footprint, while writes avoid seeks. Generating a view takes O(N), where

N is the total number of rows in the view. However, querying a view is very

quick, as the B-tree remains shallow even when it contains many, many keys.

Reduce functions operate on the sorted rows emitted by map view functions. CouchDB’s reduce functionality takes advantage of one of the fundamental properties of B-tree indexes: for every leaf node (a sorted row), there is a chain of internal nodes reaching back to the root. Each leaf node in the B-tree carries a few rows (on the order of tens, depending on row size), and each internal node may link to a few leaf nodes or other internal nodes.

The reduce function is run on every node in the tree in order to calculate the final reduce value. The end result is a reduce function that can be incrementally updated upon changes to the map function, while recalculating the reduction values for a minimum number of nodes. The initial reduction is calculated once per each node (inner and leaf) in the tree.

When run on leaf nodes (which contain actual map rows), the reduce function’s

third parameter, rereduce, is false. The arguments in this case are the keys

and values as output by the map function. The function has a single returned

reduction value, which is stored on the inner node that a working set of leaf

nodes have in common, and is used as a cache in future reduce calculations.

When the reduce function is run on inner nodes, the rereduce flag is

true. This allows the function to account for the fact that it will be

receiving its own prior output. When rereduce is true, the values passed to

the function are intermediate reduction values as cached from previous

calculations. When the tree is more than two levels deep, the rereduce phase

is repeated, consuming chunks of the previous level’s output until the final

reduce value is calculated at the root node.

A common mistake new CouchDB users make is attempting to construct complex aggregate values with a reduce function. Full reductions should result in a scalar value, like 5, and not, for instance, a JSON hash with a set of unique keys and the count of each. The problem with this approach is that you’ll end up with a very large final value. The number of unique keys can be nearly as large as the number of total keys, even for a large set. It is fine to combine a few scalar calculations into one reduce function; for instance, to find the total, average, and standard deviation of a set of numbers in a single function.

If you’re interested in pushing the edge of CouchDB’s incremental reduce functionality, have a look at Google’s paper on Sawzall, which gives examples of some of the more exotic reductions that can be accomplished in a system with similar constraints.